Painting Reality

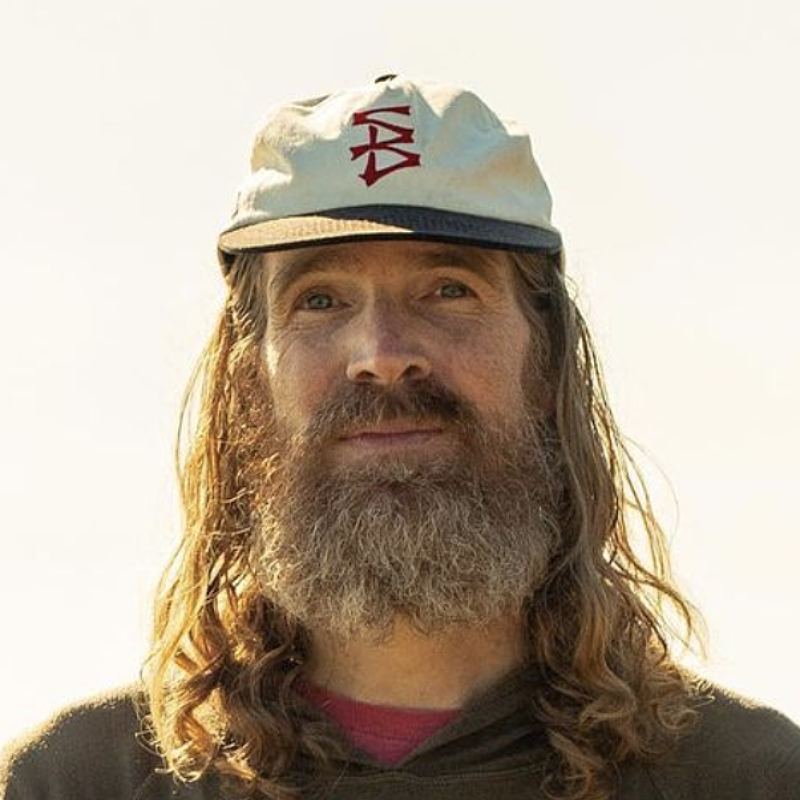

Celebrating the Mundane with Montana’s Andy Cline

BY:

Ethan Stewart

This story was first published in Issue #26, buy your copy: HERE.

For the uninitiated, Andy Cline is a painter, not a photographer. A cursory scope of his portfolio might leave you thinking that he is, in fact, an artist who creates with the camera, especially if you peep one of his landscapes or highway views from across the room. But his is a language of brush strokes on canvas boards, not f-stops and light. Such is the radical realism of his art.

Born and raised in Red Lodge, MT, Cline, who has an MFA from the University of Montana, paints pictures of moments you will instantly recognize and resonate with if you have spent any real amount of time in the Last Best Place. Trash cans thrashed about by a bear, a decomposing slab of roadkill on the side of a lonely highway, old cars rotting into a vibrant pastoral landscape, porta-potties with a view, rusted out double-wides, snowy peaks and tractor trailers parked at a rest stop- these are the things that capture Cline’s eye. He wrings the romance out of the mountains west and lets it die in the dirt. He captures the mundane with the accuracy of a historian, and yet, through his own unique sorcery, Cline is able to combine vantage point, subject, and juxtaposition in such a way that the finished product sparkles with an urgency and magic all its own. Nostalgia for the now, if you will.

A father of two young girls, Cline nowadays calls Missoula home, but family trips back to Red Lodge are frequent. The 400-mile rambles often serve as a form of interstate inspiration for the painter; the nameless dirt turnouts, the small towns, the rural highways, the quiet, forgotten moments of a state in transition all conspire to capture Cline’s attention. His intrigue is in the irony. “I am interested in the intersection of reality and pristine,” writes Cline. “We want to protect and preserve this place AND we want to access it. We live here. What does that look like?”

Change is hard, and romanticizing the west is easy.

Andy Cline

Bomb Snow: How did you come to this style of art?

Andy Cline: It was shortly after graduating in 2003, while on a road trip across Montana with my girlfriend (now wife). Oddly enough, I didn’t really paint much while I attended art school at University of Montana. I started taking pictures with my camera through the windshield of our car as we drove down backroads on that trip. Really, it was just an attempt to pass time. But, after I developed a few rolls of film, I had this one image that I thought would make a “real nice” landscape painting. However, after laying it out and blocking in my canvas with the first layers of paint, I could tell that I was correct in my earlier assumption: “Yep, this is gonna make another nice yet boring-ass landscape painting that could be of anywhere or nowhere, and who’s gonna give a shit about this?” So I took another look at the original photo, and realized I was missing the most important part of the image: the highway! All of a sudden, my landscape became a place that I recognized immediately. I had grown up looking out the window at this painting my entire life.

BS: Your art feels like a breath of fresh air when taken alongside some of the more traditionally romantic renderings of the west. Are you simply trying to reflect contemporary Montana?

AC: My snowboarder self wants the powder field with the perfect pitch and those first few turns. My painter self calls attention to resource overuse and the tension between backcountry exploration and assorted manmade environmental impacts. The scenic pullout might actually be a Town Pump outside of Butte, the pristine forest is probably on fire, etc. Change is hard, and romanticizing the west is easy. The cowboy now checks the pastures from a car instead of a horse; people want to build a house in front of that mountain view. My paintings are really about the developing west, tourism, and the climate crisis. On family road trips, I might need to pull over to take pictures of a porta-potty by the river or a dead deer along the road. I think most of us imagine ourselves playing in the mountains in our spare time. You know, getting away from everyone and finding that perfect campsite, that secret fishing spot, or that single track to ride. But I like to document the reality of the journey to and from adventures.

BS: If you had to describe your painting style/subjects to a stranger sitting next to you on a barstool, what would you say?

AC: As an introvert, I can’t imagine myself at a bar talking to a stranger. (Laughs). Maybe, after a few, I’d have the liquid courage to describe my work as “representational paintings.” If you look close, you can still see the brushstroke. It’s very close to photorealism, but not quite that refined. I paint on a smooth panel, so there isn’t even the texture of a traditional canvas. They are frameless, and the paint bleeds all the way to the edges. At first glance they look like photos on the wall, and most viewers will often take a lap through a gallery of my work keeping their distance. Once they find out that they are actually paintings they’ll take a second look, often searching for proof of a brushstroke. I hope the juxtaposition of the traditional landscape with the realities of actually living in that landscape challenges the viewer to reconsider things they speed by every day. One of my favorite aspects of witnessing people view my art is when they recognize the highway corner or the spot where farmland turned into a development. They’ll excitedly tell me their story about that place, and then my painting becomes an experience we share. It’s like when I meet someone who was also there that one time in 2003 when Bridger Bowl got 68 inches in 24 hours…The serious imagery [of my work] is often combined with a tongue in cheek title to give clues as to what I was thinking for that painting, and to maybe lighten the mood. For example, one painting with the Anaconda smelter in the background is titled “Landscape with an Erection,” while in the foreground of “Oh Deer” a dead deer lays on the side of a highway.

BS: How long does a painting of this sort take you? What’s your work flow like?

AC: Each painting takes a fair bit of time to complete depending on the image and size. I work from photos because I am capturing an exact place at an exact moment. I like to study that moment. In all honesty, the original pictures really aren’t that impressive, but I’ve always had a knack for mixing color and building rich texture through layering oil paint…Smaller pieces take about a month or two, while larger paintings can take over a year. I’m not actually a full-time painter; most of my time is spent working as an electrician. Turns out having a couple of kids and wanting them to grow up skiing and mountain biking is sorta expensive. I recently opened my own electrical construction company. We also have a couple of vacation rentals and a long-term rental in Missoula. Finding time to paint is always a challenge, and especially so after having kids. You learn to be very efficient with your time and energy. My windowless studio is in the basement of my house and is about the size of a closet (5’x6.5’). When the kids were younger, I’d wake up around 4am to paint before heading to work at 7. Covid has definitely thrown me off my rhythm, though, as my electrical work and my wife’s business both picked up at the same time that the kids were stuck staying home all the time. Needless to say, my production in the studio has slowed to a crawl, and I’m currently averaging a painting or two a year. But I am looking forward to finding more time to paint soon.

The cowboy now checks the pastures from a car instead of a horse; people want to build a house in front of that mountain view. My paintings are really about the developing west, tourism, and the climate crisis.

For more info about Andy and his art, find him on Instagram at @andycline

or check him out at the Radius Gallery in Missoula, www.radiusgallery.com/artists

MORE FROM BOMB SNOW

MORE FROM BOMB SNOW